The national costume of Azerbaijan is the result of the material and spiritual culture of the people, which has passed a long and very complex way of development. Clothing, firmly connected with the history of the people, is one of the valuable sources for studying its culture. Clothing is one of the most stable ethnic features, reflecting the national character of the people more than any other element of material culture. Playing an important role in identifying ethnogeny, cultural and historical relations, the mutual influence between nations, clothes are also influenced by economic and geographical conditions.

Historical, ethnographic, and artistic features of folk art are reflected in clothes. It may be apparent on clothing and accessories, as well as on embroidery and weaving art.

During archaeological excavations in Azerbaijan, bronze needles and awls dated to the Early Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC) were discovered. These findings prove that the ancient population of Azerbaijan could sew clothes for themselves. Small clay statues (2nd millennium BC) found in Kultepe and seals and fingerwares (5th century BC) discovered in Mingechevir give a certain idea of garments of that period. Remains of clothes made of silk fabrics were found in Mingechevir catacomb graves (5-6th centuries AD). Gold accessories and clay shoe shape dishes dated back to the 3-4th century also prove that the Azerbaijanis had high material culture since ancient times.

During restoration works in a mausoleum next to the Shirvanshah Palace (15th century) in Baku, remnants of valuable moire and silk fabrics were found.

Abundant raw materials in Azerbaijan created favorable conditions for manufacturing silk and woolen clothes here in the Middle Ages.

In the 17th century, Azerbaijan was an important sericulture region of the Near East, while Shirvan was the main sericulture province of Azerbaijan. Shamakhi Shabran, Arash, Gabala, Javad, Agdash, and other cities were Azerbaijan's main textile centers. The famous traveler Adam Olearius wrote: "They (Shirvan people) are mostly engaged in yarn, silk and wool weaving, embroidery." Textiles manufactured in Shamakhi became well known since there was a constant demand for elegant headcovers and other weaving products.

Ganja, Sheki, Nakhchivan, Maragha, Marand, Arash, and Ordubad were important textile centers. An important silk textile center, Ganja should especially be mentioned. Evliya Chalabi (XII century) wrote that the Ganja silk was very popular. The production of the cotton fabric also played an important role in the existing handicrafts in Ganja.

The production of various types of fabrics was concentrated in Tabriz. The city was especially famous for the production of high-quality velvet, satin, fabric, and keji (thread made of cooked cocoon). Some of these fabrics were even exported to other countries.

Skillful weavers of Nakhchivan manufactured inexpensive, but beautiful cotton fabrics of high quality, which were widely demanded. There was a great demand for the colorful chintz (multicolored cotton fabric with a glazed finish) they made.

Thus, in the XVII century, some specialization appeared in the field of fabric production in Azerbaijani cities continued in subsequent centuries. Among the fabrics produced and widely used in Azerbaijan and exported to other places, such as zarbaft (fabric mixed with gold), khara (bright silk fabric with patterns), atlas, taffeta, ganovuz (an elegant silk fabric, mostly colorful), kamkha (a type of patterned silk fabric), kiseya (thin transparent fabric), velvet, darayi (dense fabric woven from thick silk thread), mahud (printed wool or semi-woolen fabric on the upper side), shawl, tirma (precious woolen shawl fabric woven from wool or silk in the East), mitgal (stiff thin cotton fabric), bez (thick cotton fabric), etc. it should be noted. Some of these fabrics were popular among the people under the names "Look at me, pilgrim", "Day and night", "Stand aside", "Burnt inflame" etc.

Undoubtedly, the fabric is one of the elements reflecting national culture. Patterns and colors of fabrics distinguished one nation from another, also different classes and groups within the same nation. In Azerbaijan, ganovuz, darayi, mov, zarbaft, khara (moire), satin, velvet, taffeta, fay (dense silk or wool fabric with transverse and fine stripes), tirma (fine hand-woven wool), and other fabrics were widely used among the population.

While women's clothing was mainly made of silk and velvet, men's clothing was mostly made of mahud and homemade shawl fabric.

Both men's and women's underwear were made of linen and cotton. However, in wealthy families, underwear was often made of silk.

The XVI and XVII centuries were rich in development for Azerbaijani clothes.

Researches show that a real school of national clothing was created at that time. A person's age, occupation, and social status could be identified by his or her costume. Among the Azerbaijani costumes of the XVI century, the most interesting were the headdresses.

It is known from history that in the XVI century Azerbaijanis were called "Gizilbashlar"(Redheads) in reference to their red headgear. They wore a thin and high red cap and wrapped it with yellow fabric around it. Royalty and high-ranking military personnel adorn the turban with twelve stones or decorate it with golden lines.

The headwear has worn by high-ranking nobles sometimes had a large and valuable jewel in the center and a relatively small amount of jewels around it. Here, the big jewel is a sign of the Prophet Muhammad or Ali, and the small jewels are a sign of the 12 imams. (twelve-gored cap, symbolizing the twelve Shiʿite imams)

The famous Uzbek scientist who studied the headdresses of the Safavid period Q.A.Pugachenkova and the German scientist H. The Hots proved that their headdresses changed their shape several times, starting from the beginning of the XVI century till the end of the century. According to them, from the beginning of the XVI century until 1535, this headwear continued, and from the second half of the XVI century, it began to decrease. This type of headwear, which was fashionable till the end of the XVI century, was especially widespread in Tabriz, Nakhchivan, and Shamakhi cities.

In the XVI century, along with sharp tip red turbans, there were also ordinary non-decorated turbans in Azerbaijan.

At that time, the most common turbans were white. The Shah, vizier, or high-ranking priests would put green ones.

In the XVI-XVII centuries in Azerbaijan, along with the chalma, there were hats similar to the original small hat.

In the XVI-XVII centuries, there were hats of different forms in Azerbaijan. Among them, hats sewn from sheepskin are relatively widespread. They wore it mainly in areas engaged in cattle breeding and sheep breeding.

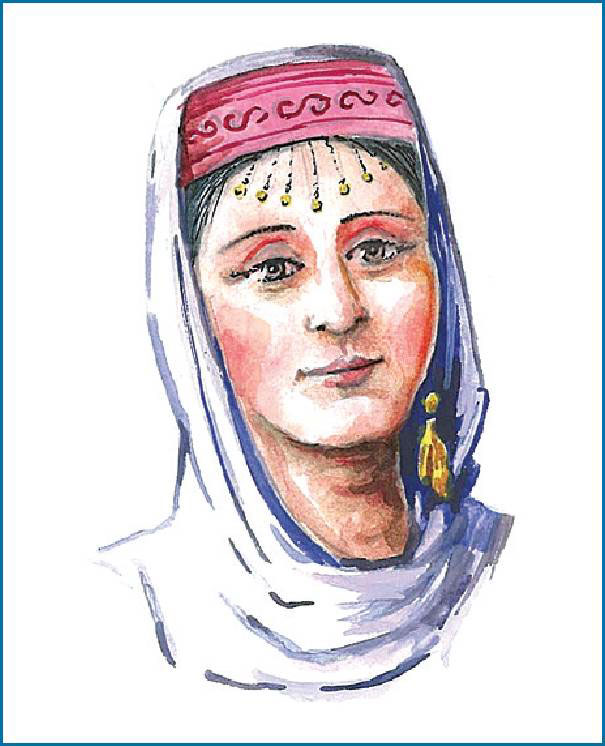

In the XVI-XVII centuries, women's headgear is also different in Azerbaijan. According to the materials, it can be said that at that time there were about seven types of women's hats in Azerbaijan. These include beautiful, colorful patterned large headscarves, small narrowly patterned arakhchins (a small close-fitting cap without a brim, skullcap), hats made of fur or velvet tied under the chin.

One of the most common women's headwear in the XVI-XVII centuries was arakhchin. There were two types of arakhchin for women and girls.

Headgears were worn by women at home, in the yard, and at guests' houses. When going outside they would usually wear a white charshab (veil). Traditionally, little girls and old women were allowed to not wear charshab outside.

The upper clothes of the XVI-XVII centuries were quite diverse and colorful in Azerbaijan. At that time, top clothes developed as a continuation of mostly ancient clothing traditions. However, their decoration was gradually enriched and sophisticated. The main changes evolved in details, patterns, and decorations.

In the XVI-XVII centuries, men belonging to a relatively wealthy class of Azerbaijan wore robes with patterned laps, shoulders, and collars. These robes had two types. The first type of robe was to be worn on the shoulder.

The second type of robe, on the other hand, was a narrow half-sleeve and relatively tight at the waist.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the traditional outer garment, the aba, was also very popular in Azerbaijan. Unlike the abas of the previous period, they sat tightly on the body, and the arms were relatively narrow. In miniatures of this century, we see that the laps of such abas were pierced with a belt.

Men wore narrow-legged trousers, which gradually widened upwards. Pants were also sewn from the material of the upper shirt, but the color was often blue or dark yellow.

Men's shoes of these centuries also had different shapes. The most common men's shoes were non-heeled (sometimes low-heeled) long neck, light boots made of soft leather.

In the XVI-XVII centuries, women's outerwear was different in Azerbaijan. However, this form of clothing reminds men's clothes of that time.

Like men, women wore long-sleeved robes to decorate their shoulders. But women's robes were simpler and less decorated with patterns.

One of the women's clothing, which was worn massively in the XVI-XVII centuries, was trousers that were long to the ankle. Like men, women's trousers were very narrow from the side of the foot and wide from the top.

Azerbaijani clothes were very colorful in the XVIII century. The formation of such independent khanates as Baku, Guba, Shamakhi, Karabakh, Nakhchivan, Ganja, Lankaran, Sheki, etc. had a significant impact on clothing. The different political and economic situations in khanates influenced changes (albeit superficially) in clothes. The changes were mostly found in textile and decorations, not in cut style and shape.

In the XVIII century in Azerbaijan, men wore a tight-fitting chukha with long sleeves. Chukha was sewn mainly from dense fabric. Depending on the person's age, the color and height "chukha" would be different.

In the XVIII century, aba was worn mainly by mullahs and respected elders.

In the XVIII century, men's footwear was also very diverse. The most common shoes for men were small flat shoes made of leather. At that time, among the wealthy people, thin leather high-neck boots were worn, and some shoes were worn by peasants from the past until the beginning of the XX century.

In the XVIII century, women's clothes were made more beautifully and elegantly. The traveler Marshall von Biberstein, who was in Azerbaijan in the late XVIII century, admired local women and their clothes.

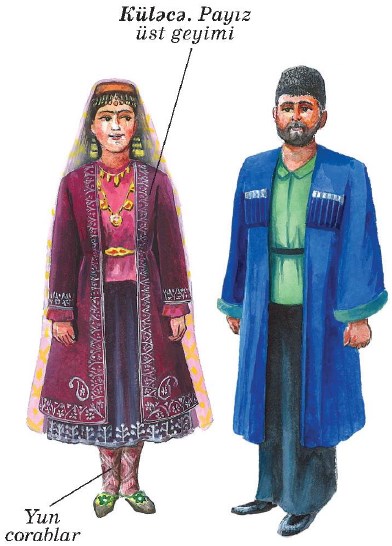

In the XVIII century, women's outerwear consisted of a shirt, chepken(outerwear worn over a shirt), arkhalig (a long tight-waist jacket), kurdu (woman´s sleeveless jacket, usually padded or fur-lined), kuleche (pleated skirt), labbada (lined jacket over the shoulder), eshmek (lined jacket over the shoulder usually made of velvet), and bahari (ornated, lined outerwear).

Depending on their age, the color of the upper shirts worn by women was also different. Girls and women wore yellow, red, green, and older women wore white or black upper shirts.

One of the most beautiful outerwear for women of this century was the chepken (a long shirt with split sleeves with a silk ribbon sewn around the edges). It had convex parts on the sides below, called "chapig" (slit), which made the body look more beautiful and figured.

One of the most popular clothes among women was arkhalig. Arkhalig was lined as chepken and it had the long tight-waist jacket. The skirt of different widths was sewn with frill or pleat in the lower part of the waist. Some of the arkhaligs had wide and straight cuts, and there were slits on the sides.

In this century, the most beautiful women's arkhaligs were sewed in Shusha, Sheki, Nakhchivan, and Shamakhi.

One of the richest women's outerwear was kurdu in this century. The kurdu was bandaged and sleeveless. Because it was worn in the winter, fur was sewn on its neck, collar, and skirt.

Although women's shoes looked like men's shoes in the XVII century, they were more elegant and abundantly decorated. Shoes of noblewomen had outer embroidery and a silver piece with ornaments (examples of such women's shoes can be found in a number of museums in our country).

In the XVIII century, women's headwear was as diverse as in previous periods.

Women would use gauze and linen to gather hair together. It has also been thought to reduce perspiration (in Gashband-Nakhchivan). They were mostly made of gold, and gold coins with hooks were attached to the ends. The gauze was made of white cotton fabric, and the chargat was orange, purple, and sometimes fringed. Due to the development of sericulture, kelaghayi was mainly used, and this headdress was unique for Azerbaijanis. Embroidered with original buta patterns. The bright colors of kelaghayi were preferred. Kelaghayi can be tied in various ways. Kelaghayi was tied over a triangular headscarf after collecting hair with a piece of gauze. As a result, there would be three headdresses worn simultaneously: first, the juna (gauze), then the kelaghayi, and finally a triangular headscarf called kasaba, sarandaz, or zarbab. In cold weather, shawls (tirma shawl, kashmiri shawl, hand-woven shawl from natural wool) were put on over this clothing.

Archaeological and ethnographic studies show that the history of silk in Azerbaijan is closely connected with the emergence of the Great Silk Road.

In many works of Azerbaijani poets, silk is mentioned as a fabric worthy of kings, the most delicate feelings, the best human qualities, female beauty are likened to silk. And this is not accidental. Processed silk is distinguished by its exceptional properties due to its nature. Silk thread is very thin, but at the same time very durable, light, like air, but woven fabrics from it can be thick, heavy, and stiff. It's unbelievable, but silk is warm in the cold, cool in the heat, does not rot, is long-lasting and durable.

The transition from color to color of silk fabric pleases the eye with its slightly matte sheen, brings comfort to a person, and its rustling awakens feelings and gives wings to dreams.

The use of silk in clothes and the interior is a sign of exquisite taste and prosperity.

Kelaghayi occupies a special place among silk products in Azerbaijan.

This square-shaped silk headdress is decorated with stamp patterns and painted following the spirit of the events taking place in life. These conditions are important for the transformation of the headscarf into kelaghayi. Kelaghayi is a symbol with great ethical and aesthetic potential.

If we look at the way of life of any nation, we always come across traditional images of women and clothes, and, undoubtedly, one of the important elements of these clothes is the headscarves. Some women use a scarf to cover their heads, others throw it over their shoulders, and in some cases the scarf turns into a fabric and takes on a universal shape, covering the head, shoulders, and body.

There is a unique element in the traditional clothes of Azerbaijani women for more than three centuries — "Kelaghayi", whose name is impregnated with the ray of ancient times.

The unique and traditional women's headdress "Kelaghayi" appeared about 300 years ago. Scientists believe that this is the age of an embroidery machine preserved in the ancient village of Basgal in the Ismayilli region of Azerbaijan. The shapes and metal molds used to create hot colors and wax patterns have a 200-years old history.

The most common plots in the 19th and 20th centuries are peacock paintings, leaves, and flowers combined with intricate geometric patterns.

Kelaghayis of each region differ from each other by their ornaments: Large patterns are characteristic for Absheron and Sheki, small patterns are used in Shamakhi, and a combination of large and small patterns is used in Ganja, Gazakh, and Karabakh regions.

Every Azerbaijani knows kelaghayi from childhood. Our grandmothers for sure had a few silk scarves. The magic patterns on the delicate silk attracted the children's attention and brought them closer to the national colors and rhythms.

Today, kelaghayi is given a new breath. Kelaghayi is so well adapted to the wardrobe of modern and fashionable women that all our fashion designers use it in their collections. Our women are very happy to receive and use this traditional headscarf with unique beauty. Kelaghayi adorns even the most ordinary dress and becomes its essence.

Azerbaijani national dresses are distinguished for their originality and uniqueness. In this sense, he managed to attract the attention of the world. In 2014, the traditional art and symbolism of kelaghayi were included in UNESCO`s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

One of the most common headgears in this period was arakhchin. However, these arakhchins differed from arakhchins of XVI-XVII centuries in the absence of a braid bag on the back.

In the XVIII century and later in Azerbaijan, a headdress made of "tasakqabagi" was widespread. These headpieces, which adorned most women's foreheads, were made by jewelers, not by tailors.

This type of headgear was widespread mainly in Karabakh, Ganja, Gazakh, Tovuz, and Borchali regions.

Paintings by Russian artists Vereschagin and Gagarin, who in the XIX century traveled to Baku, Shamakhi, Sheki, Ganja, Kazakh, and other cities also expressed admiration by the Azerbaijani national costume.

The territory of Azerbaijan can be divided into several historical and ethnographic regions. These include Guba-Khachmaz, Absheron, Lankaran-Astara, Shamakhi, Karabakh, Nakhchivan-Ordubad, Gabala-Oguz, Sheki-Zagatala, Ganja, and Shamkir-Gazakh zones. The same clothes worn by the Azerbaijanis in the above-mentioned ethnographic regions prove that they historically belong to the same ethnic group. Slight differences in costume reflected only local patterns of the common national clothing.

The costume reflected local peculiarities of Azerbaijan's various historical and ethnographic regions, clothes, indicating the age, marital and social status of its owner. The clothes of a young girl and a married woman were visibly different. Young women wore richer and more beautifully decorated garments. Clothes of girls and older women were less decorated.

Men's clothing was the same in the historical and ethnographic zones, as women's clothing. It was not hard to determine by his clothes what class he belonged to.

Children's clothing in shape was identical to the clothing of the elderly, differing only in size and elements of adaptation to the age characteristic.

Unlike daily and working clothes, wedding and special occasion costumes usually were made of precious fabrics and decorated with golden and silver jewelry.

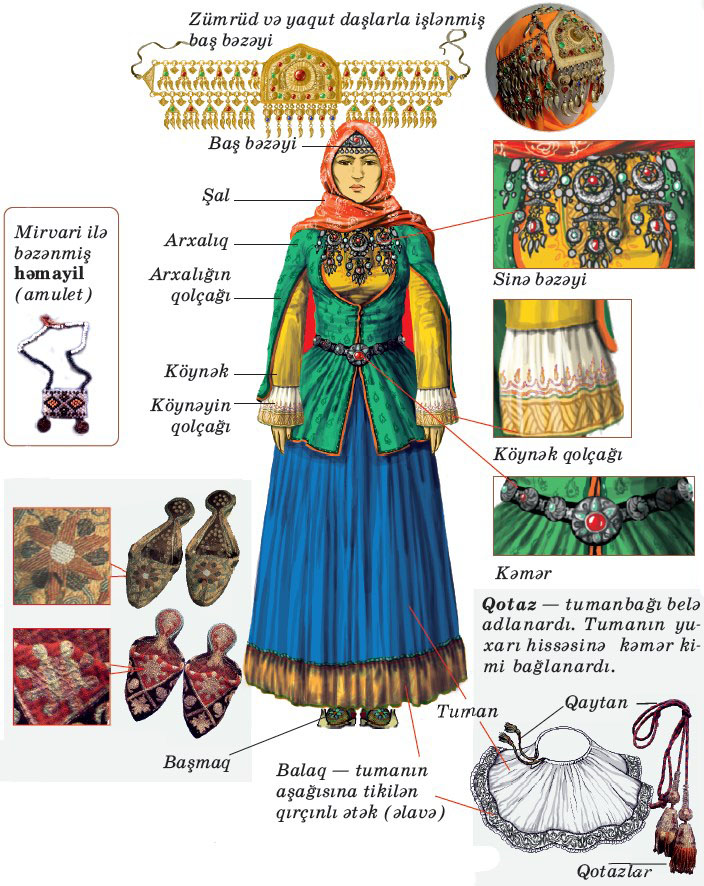

Azerbaijani women's clothes consisting of upper and lower pieces dated XIX and early XX century could be divided into two groups.

The upper garments comprised upper shirt, chepken, arkhalig, labbada, kulaja, kurdu, eshmek, and bahari.

The sleeves of the women's upper shirt were mostly long, wide, and straight. The part of the arm sewn to the shoulder was mostly straight and in some cases small-pleated. Khishdek (a patch of fabric in a different color) was usually placed under the armpit. The shirt was buttoned with one button on the neck. The upper shirt was usually sewn from ganovuz or fay. The neck, collar, cuffs, and hem of the shirt were covered with yellow bafta (braided narrow ribbon for decoration). The front of the shirt was embroidered with a gold or silver coin.

Chepken was worn over the top of the shirt. It had a lining and was sewn tight to the body. On the sides, it has bulging parts named "chapig" (slit), which showed the body nicer and more attractive. There were so-called sleeves ending with so-called gloves. These sleeves were dangling loosely from the shoulder. Sometimes buttons were also sewn into this so-called sleeve. The chepken was made of tirma, velvet, and various gilded fabrics. Sarima, bafta, koba, zencire, shahpesend was sewn into the collar of chepken, to the edge of a slit, to the edges of hem, and the edges of the sleeves.

Arkhalig was the most popular costume among women in Azerbaijan. There were many types of it.

Like chepken, arkhalig also had a lining and was tight to the body. Skirts of different widths were sewn with ruffles or pleats at the bottom of the waist. Some arkhaligs were wide and straight and the side part had slits. The shape of the sleeves of the arkhalig was also different. Some were straight and long, and it was sewn in the form of a so-called arm that ended with a glove below the elbow. The third form of the arkhalig was lelufar-sleeved. The lelufar sleeve was straight to the elbow and a lily-shaped slit below the elbow. Along the hem of the sleeve, there are two finger-width pleats made of arkhalig's fabric. The collar of the arkhalig was open. In most cases, the arkhalig were buttoned from the breast to the waist. Some of them were unbuttoned at all. The arkhaligs were made of velvet, tirma, and various gilded khara fabrics and decorated with different bafta and sarima.

Lebbade was quilted and lined. The lebbade collar was open, and at the waist, it was tied with a braid. There were shortcuts on the sides just below the waist. Lebbade's sleeves were short, usually down to the elbows. Lebbade was sewn from tirme fabrics, velor, and various shiny fabrics. The collar, sleeves, and hem were trimmed with delicate bafta.

Eshmek is quilted outerwear. Eshmek's chest and armpits were cut open, and the sleeves were down to the elbows. For sewing eshmek, as a rule, they used tirme and velor. The inner part, collar, sleeves, and hem of the eshmek were trimmed with fur. In addition, baffles and chains were sewn to the sleeves, hem, and collar of the eshmek.

Kurdu is a quilted women's garment with open collars, sleeveless. It has slits on the sides. The kurdu was sewn from tirme and velor fabric. A particularly widespread type of this clothing was the so-called Khorasan kurdu, which was made of dark yellow leather with patterns embroidered with silk thread of the same color.

The bahari was a lined, quilted woman´s garment for the upper body. It was closely fitted at the waist and fanned out below the waist. The elbow-length sleeves were cut straight and the collar was left open. It was mainly made of velvet. Various bafta, koba, and chains were sewn on the collar, skirt, and sleeves of the bahari.

Kulaja is a woman's outer garment with a pleated skirt. The sleeves were straight and finished a little below the elbow while the collar was left open. The kulaja was mainly made from velvet and tirma. Different decorative techniques were used on the kulaja, including gulabatin (golden or silver embroidery), bafta (using braid or lace trims), zanjira (fine needlework), munchuglu tikma (beadwork), and pilakli doldurma (quilting).

The length of the tuman (layered skirt) worn by the Azerbaijani woman was up to the ankle, except the Nakhchivan-Ordubad zone. In the Nakhchivan-Ordubad zone, women wore relatively shorter tuman's (skirt). Tuman was made of silk or wool with different patterns. In addition to the upper skirt, the skirts worn under it were called layers of tuman. Tumans could be goffered or pleated and had a waistband at the waist. On both sides of the waistband, which was woven from goat's fur, there were tassels made of colored silk and gulabatin threads. Tumans were made of all kinds of fabrics, from chintz to tirma. Kobas, chains, and various baftas from different fabrics were sewn to the hems of tuman. In some cities, women also wore chakhchur. Chakhchur was made of various silk fabrics.

To make women's outerwear even more beautiful, there were various baftas, sarima, garagoz, zenjire, and shahpesend made at home or in craft workshops. Buttons made of gold or silver were sewn along the collar of women's clothes. Sometimes golden coins were added to the edge of the shirt. Gold threads, beads , and other kinds of embroidery were also very common. Gulabatin, munjug, pilak, and other embroidery were also widely used in women's clothing.

Women usually wore a golden or gilded silver belt over arkhalig or chepken. Moreover, leather belts with silver coins and silver buckles were also widely used.

Kelaghayi, various kerchiefs, naz- naz, and gaz-gaz silk veils were the most popular women veils. Kelaghayi was manufactured in special shops of famous sericulture centers, such as Sheki, Ganja, and Shamakhi.

In some regions, women wore arakhchin under the headscarf. These arakhchins were often decorated with gold ornaments of various shapes.

.jpg)

Charshab was typical for women of some towns and suburban villages. When leaving the house, women put on charshab. It was made of colored satin, checked felt fabric, and various kinds of silk fabrics. Women covered in charshab sometimes wore also ruband.

The national dress of Azerbaijani men of the XIX century also consisted of upper and lower clothing.

Men's outerwear consisted of an outer shirt, arkhalig, chukha, and trousers. It should be noted that such a set of widespread national clothes, with minor differences, was characteristic of the entire territory of Azerbaijan.

Men's outerwear consisted of an upper shirt, the upper men's shirt had two cuts: with a collar in the middle and on the sides. The shirt collar was fastened with a button or a loop. The men's shirt was sewn mainly from atlas fabric and satin.

The Arkhalig was distinguished by its tight fit to the body. Its hem was ruffled, the sleeves were straight, gradually tapering at the elbow. The arkhalig were sewn with one or two pockets and fastened to the neck. Materials such as cashmere, atlas, satin, silk, velvet, etc. were used for sewing arkhaligs. Over the arkhalig, young men wore a belt, and old men wore gurshags.

Chukha is one of the men's outerwear. There were two chukha types in Azerbaijan-vaznali chukha and charkazi chukha. Chukha had a straight sleeve detachable from the back and the sides, its hem was thickly gathered. The collar of both types of chukha was cut open.

The chukha sleeves were cut straight and long, and so-called "hezines" were sewn to each chest for "luck". These "hezines" were worn with "luck" decorated ornament with silver or gold.

Another type of chukha — "cherkezi" differed from "vaznali" in its cut. The lining of the overhead sleeves of the cherkezi chukha was sewn from silk fabric, buttons or loops were sewn along the entire section of the sleeves.

Men's trousers had a relatively large top that tapered towards the side of the leg. A piece of fabric of a triangular shape was sewn between the legs of the trousers. Waistband is made of goat fur sewn around the waist of the trousers. At the ends of the waistband were tassels made of beautiful gold and silver gulabatin. Men's trousers were sewn from homespun shawls or woolen fabrics of different varieties.

In some mountainous areas, winter outerwear for men was a sheepskin coat sewn from sheep's skin with buttons on the collar. Some men wore Khorasan fur coats decorated with patterns embroidered with silk thread. In mountainous areas, shepherds wore yapinchi in winter.

In Azerbaijan, special attention was paid to men's headdresses. It was considered indecent to go without a headdress. The most widespread types of men's headwear were hats made of leather of various cuts: bukhara and cherkezi hats (sewn from black, gray, or brown skins), shele-hats. Arakhchins, sewn from "tirma" fabrics and silk fabrics, in most cases decorated with gold embroidery, was very widespread. Elderly men and old people wore under their hats quilted "tasak" made of white coarse calico, and at night quilted "shebkulakhs".

One of the most widespread types of clothing in Azerbaijan is knitted woolen jorabs. Jorabs were knitted from silk and woolen threads. They differed both in their fine and beautiful pattern and the coloring of the threads. The patterns of the jorabs are the same as the patterns found in embroidery, "basma" and fabrics. Jorabs were knitted long, up to the knees, and short - up to the ankles.

In Azerbaijan, shoes made of multi-colored leather - tumash - were widespread. The most common type of footwear worn by both women and men was considered to be shoes.

Women wore embroidered boots and long-neck boots. Men's shoes, made from leather or untreated leather, were usually plain and without patterns. In the cities, men wore shoes or "naleyins" sewn by shoemakers. And in rural areas, charyks sewn from untreated leather were more common. Bands for charyks were knitted from the woolen thread.

Various decorations complimented the clothing and enriched its national characteristics. Jewelers made jewelry from gold and silver. They also used precious stones: diamonds, emeralds, rubies, pearls, turquoise, agate, etc. Azerbaijan's jewelry centers were Baku, Ganja, Shamakhi, Sheki, Nakhchivan, and Shusha. Local jewelers could make all kinds of jewelry people needed. Silver belts made by Kubachi jewelers in Dagestan for men and women were also popular in Azerbaijan.

Azerbaijani women were very fond of jewelry and used them widely and skillfully.

The complete set of jewelry worn by women was called "imaret", which included various head and breast ornaments, rings, earrings, belts, bracelets, and bazubends.